In early 2019 we launched our ‘Securing Safety’ study into the rate, cost and impact of relocation as a response to extra-familial harm (EFH) in adolescence. The project is funded for three years by the Samworth Foundation and we have partnered up with Lisa Holmes and Vania Pinto at the Rees Centre to deliver the first national study into the use of relocation as a response to EFH.

In our first year we have surveyed 13 local authorities across England and Wales to establish the rate at which relocations are used, and for what categories of harm, followed with a round of interviews to understand why relocations are used and in what circumstances. Our briefing ‘A sigh of relief’ details the full findings of this study; and the dilemmas professionals face when considering whether to place a young person out of area or in secure accommodation.

Carlene Firmin made the link between relocations and Contextual Safeguarding in a 2019 paper in the journal Children’s Geographies, highlighting the tensions between extra-familial forms of harm and current child protection framework:

Safeguarding partnerships in England face a practical challenge when addressing these ‘public’ types of significant harm, when using a child protection framework designed to respond to risks within the private space of families. In the absence of a safeguarding system equipped to reshape unsafe extra-familial contexts young people have been moved away from them. (Participating Local Authority)

In 2019 the Children’s Commissioner announced that an increasing number of young people aged 12 upwards are entering the care system for the first time due to extra-familial forms of harm. We know from the various projects studied under the Contextual Safeguarding programme that relocations are being used to address harms related to child sexual exploitation and the exploitation of young people via ‘county lines’. Yet there is little evidence on the impact of these interventions on young people’s safety, or the cost to local authorities. Our study begins to address this evidence gap. (Participating Local Authority)

This lack of evidence poses practice challenges for services across the country for what are often high cost and complex interventions, many respondents echoed the thoughts of this Local Authority:

So we’ve worked really hard to improve practice so that we’re working to keep children safe in their community where we can, but there actually may be times when children aren’t safe in their communities and that we don't have the joint buy in that perhaps we would like in order to keep those communities safer. We have had to move children out of area. (Participating Local Authority)

To start to build a national picture, 13 participating local authorities took part in a manual trawl of young people’s cases open to their children and families services in September 2019 to establish how many young people were open to their service due to EFH and how many of those were in out of area placements. This was no easy task and we want to thank all participating sites and their workforce for getting stuck in to return accurate data on the issue! As one local area reported:

It was an immense task, initially we identified quite quickly that the data into the front door, during September, would be captured, we realised at that point that some of the key areas that you wanted us to report on weren’t included on the contact reasons, so that prompted a bit of work, so that was something that had to be done first. (Participating Local Authority)

All participating local areas reported challenges in establishing how many young people were open to their services due to EFH and of those how many were in out of area placements. This was largely because local areas did not have consistent recording or reporting mechanisms for EFH and there were inconsistencies in definitions and which forms of harm were traceable through case management systems.

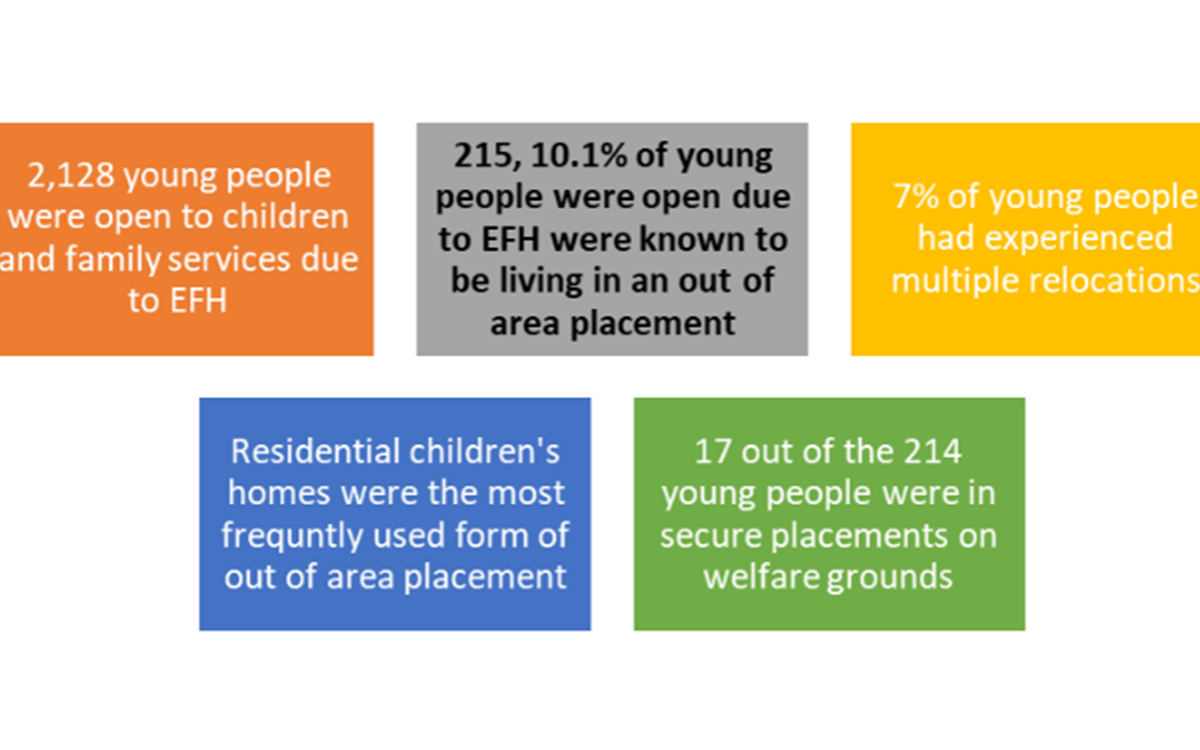

Once the data was collected this was fed back via an online survey and analysed by the team. We found that of the 13 local areas that returned survey data:

Of the 215 young people in out of area placements:

- 34 were 18+; 91 were 16-17; 83 were 13-15; 6 were 10-12.

- 111 were identified as male and 103 were identified as female.

- 123 were identified as white and 85 were identified as BAME.

- Only 6 out of 13 sites returned data on disability with 41 young people reported as having a diagnosed disability.

- 81 of the 215 young people had at least one missing episode: with 502 missing episodes in total.

As the title of this blog suggest, relocating wasn’t an easy decision for local areas.

And of course, it’s a last resort because a number of the young people are settled and it’s been quite hard, they’ve got positive attachments in their foster placements, local foster placements, and so, we’ve had long discussions about the pros and cons of moving (Participating local authority)

Local areas were conflicted around their use of relocation. We analysed their reasons for moving against Shuker’s ‘Multi-dimensional Safety’. Here’s a summary of what we found:

Physical safety

The primary justification for relocations was concern for physical safety.

If I look at the list of young people, particularly the LAC, the looked after children that are placed out of borough, I would say that all, I'd probably say that 98% of those have been placed out of borough due to concerns in relation to exploitation, their safety around serious group violence, or their criminality, without a doubt. (Participating local authority)

Relational safety

Relocations were used to disrupt harmful relationships and create opportunities for positive or therapeutic relationships. However it was noted that relocations could sever important relationships and also make it hard for services to maintain relationships with young people.

Because it takes them out of the area, it takes them away from their family, and you can't support them as well. So we've worked hard to bring children back into the authority, and so we have very few cases. (Participating local authority)

Psychological safety

Less reference was made to the psychological and emotional well-being of young people when relocation was used. A small number of sites reported moving young people specifically to access therapeutic support, or the positive emotional break a relocation can create for young people. However for those areas that didn’t use relocations, or tried not to, concerns were raised about the impact of relocations on young people’s emotional wellbeing as a result of disrupted relationships with parents, carers, friends and professionals.

We don't believe as an authority it's the right thing to do. Exploitation is everywhere, isn't it, and it's how we try to manage that. I think you're isolating children even more, and the message that you're giving to them by moving them away, you're taking them away from everything that they know. (Participating local authority)

Summarising our findings we reflect that local authorities are clearly concerned about the welfare of young people, particularly their physical safety which often drives the use of relocations. Yet there is a lack of oversight of the rate at which these interventions are used and a lack of planning to inform effective transitions into, and out of placements. Relocations will sometimes be the safest and most effective response to EFH. However, we propose that greater attention is required to explore contextual interventions that could create safety to enable young people to return to their home authority

You can read our full recommendations and plans for phase two here.